Neptune Relationships: Women Who Love “Too Much”

Women Who Love Too Much is less a book and more a mirror held up to the soul of the romantic martyr—the emotional alchemist who believes, ‘If I love hard enough, I can save them.’ And what the author Robin Norwood so brilliantly articulates—through the lens of clinical insight, is that beneath this desperate desire to love lies a realm of unmet needs, and the seductive pull of addiction disguised as devotion. Norwood invites us into a theatre where the heroine carries wounds that she mistakes for a map to salvation. Enter Neptune. The nebulous divinity of the sea, the shapeshifter, the mystic, the deceiver. How eerily apt that Neptune rules illusions, dreams, escapism, and addiction. The Neptunian energy in astrology mirrors almost perfectly the dynamic Norwood describes: the overwhelming compulsion to dissolve oneself in another, to merge beyond all reason, and to mistake suffering for significance.

Norwood doesn’t just describe patterns—she reveals a mythic blueprint. Women who love too much often have histories filled with abandonment, inconsistency, and a haunting sense of unworthiness. They enter relationships subconsciously seeking redemption through service. And if their partner is broken, addicted, emotionally distant, or even abusive—it only makes the mission feel more vital, more spiritual, more necessary. This is Neptune’s waters: “Sacrifice is holy. Stay. Love will purify.” But it’s a false gospel. And Norwood’s brilliance lies in unmasking it, showing how such love, when rooted in past trauma and unhealed wounds, becomes a form of self-erasure.

But let us not demonize Neptune, for within its illusions lies transformation. The same archetypal forces that once led a woman to lose herself in another can, when made conscious, become the very energies that lead her back to her soul. Neptune’s shadow is disillusionment—but its gift is divinity, a compassion flowing outward and inward. The key is awakening. The turning point is when the woman realizes her worth was never something to be earned through suffering—it was always innate.

In women, there is the silent epidemic of emotional martyrdom, cloaked as love, carried mostly by those who have been taught—culturally, spiritually, even mythically—that to love is to endure. And what an insidious myth it is. To idealize a partner beyond their reality, to see a broken man as a puzzle meant only for her hands, isn’t simply a romantic delusion—it is a sacrificial rite. And the altar is her own well-being. What begins as compassion—an impulse to care—mutates under the weight of addiction, both theirs and hers. Not always to substances, but to chaos, to crisis, to the cyclical drama that feels like intensity but is in fact a slow erosion of self. These women aren’t fools—they’re often intelligent, insightful, emotionally attuned—but they are captives of a pattern. A pattern where love must be proven, earned, and survived. Under Neptune’s influence, the boundaries of self blur. A Neptunian woman may literally not know where she ends and her partner begins. His moods become her climate. His pain becomes her project. His dysfunction becomes her identity. And in the background, the voice of Neptune urges, “This is divine. This is what love looks like. Stay a little longer.” But this isn’t love. This is obliteration disguised as intimacy. Norwood shows us that such love can breed real, devastating consequences: physical illness from chronic stress and emotional depletion; psychological breakdowns from prolonged cognitive dissonance; exposure to violence masked as passion; and the subtle normalization of addiction as a relational glue.

The book’s central theme, relationship addiction, explores the impact of childhood experiences on the development of certain patterns of thought and behavior in women. Norwood identifies a specific group of women who, as a response to childhood problems, exhibit what she terms as loving “too much.” The author compares these women to heroin users, jabbing needles in their arms, underscoring the severity of the addictive and potentially destructive nature of their relationships.

This is addiction. It is biochemical, emotional, spiritual. It is the rush of adrenaline when they call, the crash of despair when they disappear. It is checking your phone like a junkie checks for veins. It is the hit you know will hurt you, but you take it anyway—because not having it feels worse. Norwood’s heroin analogy isn’t gratuitous; it is exact. These relationships alter neurochemistry. They hijack the nervous system. And like any addiction, they escalate, isolate, and devastate. To truly recover, as Norwood suggests, is to trace the thread back to childhood.

Unstable and Needy Relationships #Neptune

The woman, shaped by her childhood experiences, exhibits a strong attraction to men who embody a sense of neediness. In turn, she finds fulfillment in being needed, creating a symbiotic relationship where both parties fulfill specific roles. This unconscious draw to unstable relationships and damaged men is a manifestation of the woman’s internalized patterns from childhood. The act of trying to redeem a partner through love is a common thread in these relationships. The woman may perceive herself as a source of healing and stability for her partner, believing that her love can transform him and mend the wounds of his past. However, as the relationship unfolds, it often transforms into a consuming and desperate yearning for the beloved. The partner becomes mysterious and elusive, creating a cycle of emotional highs and lows that intensify the woman’s emotional investment. The perception of the partner as mysterious adds an element of unpredictability and excitement, further fueling the woman’s emotional involvement.

Compassion and pity play important roles in how these individuals define love. The woman’s compassion becomes a driving force in the relationship, and her pity for her partner’s struggles deepens her emotional connection. This combination of compassion and pity can create a powerful emotional bond that, despite its intensity, may not be sustainable or healthy in the long run. The book explores how these patterns, rooted in childhood experiences, can lead to a cycle of dysfunctional relationships.

The influence of Neptune is depicted in the glamorization of the romantic bond. The attraction of an idealized, almost otherworldly connection can cast a spell on individuals, making them more tolerant of suffering and hardship within the relationship. Neptune, as a symbol of illusion and idealization, contributes to the creation of a romanticized narrative that may not align with the reality of the situation. The yearning for more than is available, as described in the context of these relationships, suggests an insatiable desire for an idealized version of love that may not be achievable in the current circumstances. This perpetual yearning can lead to a sense of unfulfillment and dissatisfaction, driving individuals to endure pain in the hope that their devotion will eventually be rewarded with the perfect love they envision.

The glamorization of the relationship can create a situation where the woman becomes willing to endure more than is healthy or sustainable. The distorted perception of love, often fueled by Neptune’s influence, may lead to a prolonged tolerance of pain and suffering in the name of preserving the romantic ideal. The book likely delves into the need for individuals to recognize the difference between genuine, healthy devotion and the kind of self-sacrifice that can be detrimental to one’s well-being.

The connection between a woman’s childhood experiences and her adult behavior, as discussed in “Women Who Love Too Much,” adds a psychological depth to the understanding of relationship patterns. The woman may have been subjected to eternal chaos in her formative years. which points to a challenging and potentially traumatic upbringing. In response, she might develop an overwhelming need to fix everything and take care of everyone around her. This inclination to take on others’ burdens and emotional problems can stem from a deep-seated desire for control and stability, possibly as a coping mechanism developed in response to childhood chaos. The book suggests that this pattern of behavior, characterized by an excessive sense of responsibility.

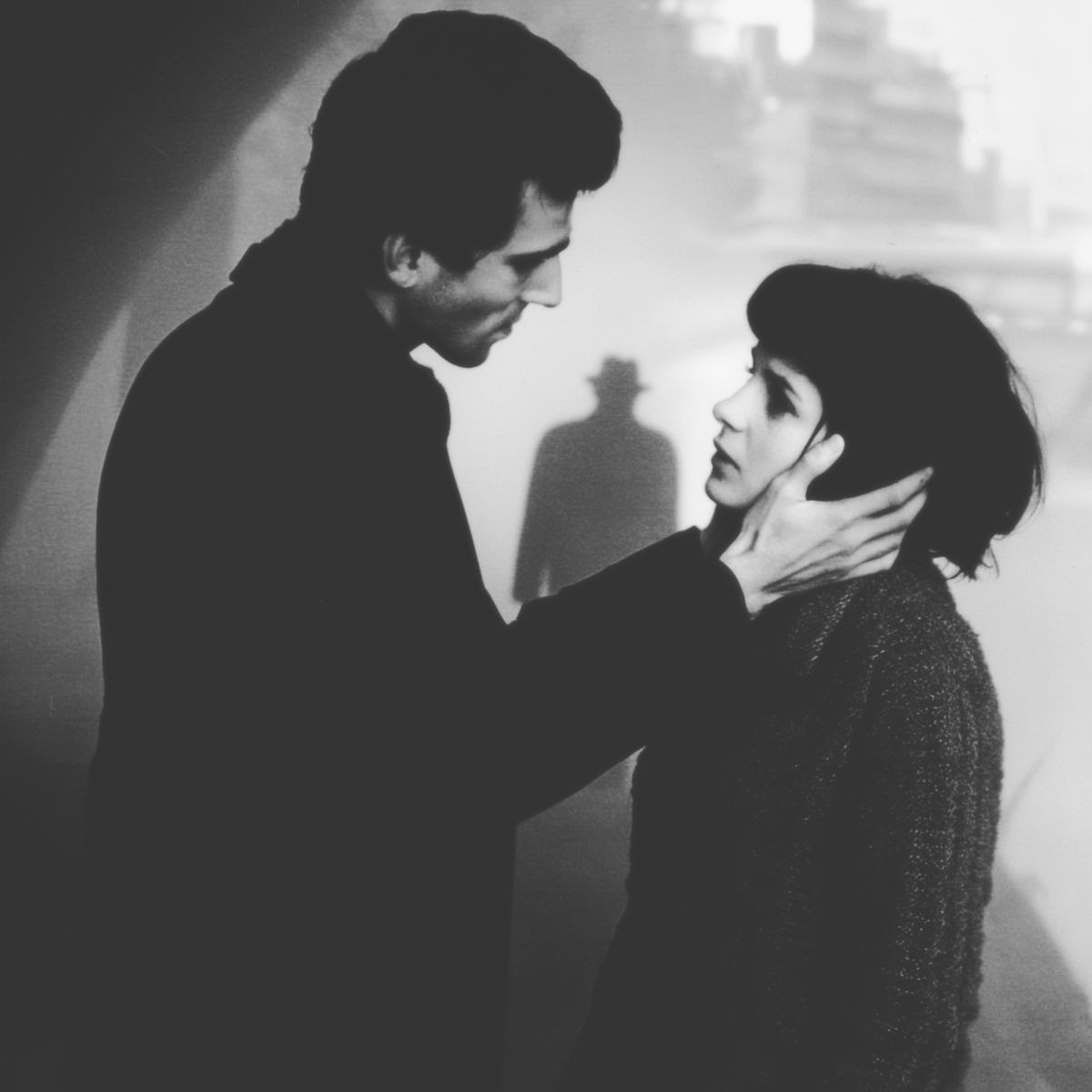

The initial dream of saving someone and seeking redemption is often fueled by the desire to heal a partner’s wounds. However, it can gradually transform into a nightmarish reality. The waters turn dark, murky, and treacherous, encapsulating the emotional landscape of these relationships. What once seemed like a source of fulfillment and purpose becomes overwhelming and chaotic. The individual, driven by Neptune’s influence, may find themselves in despair, feeling like they are slowly drowning in misery as the relationship takes unexpected and distressing turns.

The difficulty that Neptune introduces in seeing what is actually there highlights the theme of illusion and idealization in these relationships. The individual, driven by a romanticized vision, may be blinded to the true nature of their partner. The discrepancy between the imagined ideal and the reality of the person’s character becomes a source of deep disappointment and disillusionment. It creates emotional turmoil arising when Neptune’s influence distorts perceptions and holds unrealistic expectations. Falling in love with someone who turns out to be vastly different from the imagined ideal is a painful realization that can lead to a sense of loss and betrayal.

Plunging into the World of Feelings

In Women Who Love Too Much, Robin Norwood paints a picture of women magnetized to pain, drawn again and again into the quicksand of unreciprocated love, and doesn’t this relate to the Neptunian theme of sacrifice? To love not wisely but too well is almost a sacrament for the Neptunian soul. These are the people who believe love can redeem, transform, resurrect even the most broken of beings. Like Florence Nightingale with a bottle of rose quartz, they arrive at the scene, hearts wide, ready to save. But when Neptune isn’t embodied as divine compassion but confused with martyrdom, it morphs from holy water to intoxicating poison. What starts as empathy can end as co-dependence, a holy union with suffering itself.

Pisces, Neptune, and 12th house women, being ruled by mutable water, are naturally equipped for emotional osmosis. They feel what isn’t said, hear what isn’t spoken, and often, tragically, fall in love with potential rather than presence. They adore the outline of a soul and spend lifetimes trying to color it in. But love, true love—not fantasy, not projection—asks for mutual recognition, not endless sacrifice. So what’s the medicine? The Neptunian journey, when integrated, becomes one not of losing oneself in another but finding the divine within oneself.. Turning their infinite empathy inward, becoming the savior you once tried to be for everyone else.

For those touched strongly by Neptune—those born under Pisces, 12th house placements or with Neptune enshrined in prominent positions in their birth chart—this dissolving of self can feel like both a divine calling and a dangerous seduction. They are often born with a kind of emotional clairvoyance, a mystical radar that picks up the frequencies of others’ wounds, longings, and dreams. It’s isn’t that they fall in love blindly—quite the opposite—they see into the soul, the possibility, the vulnerability beneath the surface. And tragically this can be the problem. For in that depth of perception, there can be a blurring of lines: is this my desire, or theirs? Is this my pain, or am I just absorbing it? Neptunians don’t always fall in love with who someone is—they fall in love with who someone could be if only they were loved enough. If only they could be healed. If only someone—perhaps, just perhaps me—could rescue them from the ruins of their own suffering.

This is the Neptunian paradox: in trying to love others unconditionally, they can forget the conditions that safeguard their own souls. They dive headlong into the emotional oceans of others, often forgetting to secure their own life raft. They romanticize the struggle, mythologize the dysfunction. Love becomes a form of penance, devotion indistinguishable from self-abandonment. Robin Norwood understood this intimately in Women Who Love Too Much. She spoke of women whose capacity to love was boundless, but tragically tied to suffering. Women who, in their own wounds, mistook pain for passion, neglect for mystery, and chaos for connection. It’s a spiritual misdirection. A longing for transcendence misapplied to a relationship that instead of elevating, entraps.

In psychological terms, this can reflect early attachments—learning, perhaps too young, that love must be earned, suffered for, clung to. And Neptune is the great spiritualizer. It doesn’t only want love—it wants divine union. But humans are not gods. They falter, fumble, forget. And when the Neptunian gives their heart without reserve, expecting transcendence in return, they are often met with something far more mortal—betrayal, disappointment, abandonment.

At its highest octave, Neptune speaks of unconditional compassion, of spiritual love that transcends form. Yet, here’s the conundrum—it is so very easy to wear the robes of the martyr, to cast oneself as the perpetual giver, the saint of suffering, and in doing so, to wield a subtle power cloaked in sacrifice. Martyrdom, when fueled by unresolved wounds and unmet needs, becomes less about compassion and more about control. A way of shaping others’ actions, shaping the dynamics of a relationship, through unspoken debts. “Look how much I’ve given you,” says the Neptune-touched soul, not always aloud but in the soul’s undertone. “Surely now you must stay. Surely now you must love me.”

This is longing in disguise. It’s the ache for connection twisting itself into obligation. It’s the fear of abandonment, dressed in the halo of devotion. Because when love becomes a duty owed in response to sacrifice, it ceases to be love and becomes a contract, unsigned and silent, but fiercely binding.

Then there’s love addiction—an attachment to people, to emotions, to the intoxicating drama of turbulent love. For Neptune is the planet of illusion and escapism, and there’s no more intoxicating drug than the belief that your love can heal them. That if you just love hard enough, suffer long enough, wait faithfully enough, they will change. They will see. They will be saved. But this is the illusion. It’s the film on the lens, the dream mistaken for daylight. Because love is not rehabilitation. It is not martyrdom. It is not a spiritual hostage situation where one’s wellbeing is contingent on another’s transformation. The Neptune archetype asks us to dissolve, yes—but not into another person.

Neptune is a deep sea current: invisible, mysterious, and capable of pulling even the strongest swimmer into unfathomable depths. Idealization, under Neptune’s spell, is less a choice and more a compulsion. It’s not simply that one wants to believe the best in others—it’s that their soul needs to believe in it. Needs to find something holy in the mundane, to spiritualize every kiss, every wound, every reconciliation. Love becomes a kind of religion, the beloved a deity to worship. But gods, when touched too closely, have a tendency to crumble—or worse, to reveal they were never divine in the first place.

And so the Neptunian or Piscean soul, so open, so receptive, struggles with boundaries. Not just the emotional ones—though those, too, often feel like an afterthought—but spiritual boundaries, the kind that keep one’s essence from becoming entangled in another’s karma. They suffer with you. And in doing so, they lose the self that love was supposed to enrich. Yet it’s important to understand that this isn’t pathology—it is love without discernment. Compassion without containment. These aren’t flaws, but gifts that have slipped their leash. Gifts that, once reclaimed and consciously wielded, become powerful forces for healing, both within and without. So what does it mean to integrate Neptune? It means to love with eyes wide open. To hold compassion in one hand and truth in the other. To recognize that while your heart may be vast enough to contain another’s pain, it is not your job to carry it.

Venus Trine Pluto: Dark Desires

Venus Trine Pluto: Dark Desires

Mars Conjunct Pluto Synastry

Mars Conjunct Pluto Synastry

Saturn in the 1st House: From Self-Doubt to Lasting Identity

Saturn in the 1st House: From Self-Doubt to Lasting Identity

Venus Trine Mars Synastry

Venus Trine Mars Synastry

Moon Conjunct Mars Natal Aspect

Moon Conjunct Mars Natal Aspect

The Scorpio Teenager

The Scorpio Teenager

Reflections on a Past Venus-Pluto Synastry Aspect

Reflections on a Past Venus-Pluto Synastry Aspect

Venus-Pluto Synastry: A Love So Powerful That It Might Just Kill Them

Venus-Pluto Synastry: A Love So Powerful That It Might Just Kill Them

Mars-Pluto Synastry: Something Quite Dark and Dangerous

Mars-Pluto Synastry: Something Quite Dark and Dangerous

Mars in Aquarius: Sex drive

Mars in Aquarius: Sex drive

The Yod Aspect Pattern: The Mystical Power of the “Finger of Fate”

The Yod Aspect Pattern: The Mystical Power of the “Finger of Fate”

Uranus Transits: 1st House: Winds of Change:

Uranus Transits: 1st House: Winds of Change:

Emotional Understanding: Moon Trine Synastry Aspects Interpreted

Emotional Understanding: Moon Trine Synastry Aspects Interpreted

The Moon: The Goddess of the Night

The Moon: The Goddess of the Night

Sun Square Pluto Natal Aspect: I Am Titanium

Sun Square Pluto Natal Aspect: I Am Titanium

Moon Conjunct Pluto Synastry

Moon Conjunct Pluto Synastry

Venus Conjunct Neptune Synastry: Euphoria and the Aftermath

Venus Conjunct Neptune Synastry: Euphoria and the Aftermath

Pluto in Libra in the 2nd House: Lessons on Self-Worth and Financial Independence

Pluto in Libra in the 2nd House: Lessons on Self-Worth and Financial Independence

Sun Conjunct Pluto Synastry: Enlightening or Annihilating

Sun Conjunct Pluto Synastry: Enlightening or Annihilating